Nerve blocks and interventional procedures in the management of temporomandibular joint disorders: a scoping review

Introduction

Temporomandibular joint disorder (TMJD) is a complex disorder affecting the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), muscles of mastication and associated structures (1). They have various overlapping manifestations such as pain, clicking, crepitus, mandibular movement restriction, facial deformities, open lock, closed lock, tenderness of muscles, trigger points, referred and radiating pain. Understanding the etiopathogenesis, eliminating predisposing, perpetuating factors, and managing TMDs can be difficult (2). Approximately 88% of patients report complete or substantial improvement in their clinical signs and symptoms with conservative management (3). If conservative management fails, invasive surgical procedures may be considered, which has its own range of risks. Injections into the joint in the form of nerve blocks, intraarticular injections, arthroscopy or arthrocentesis are less invasive and can aid in both TMD diagnosis and management. The purpose of this scoping review is to discuss the use of joint interventions as possible, convenient, economical and minimally invasive options for TMDs.

The objective of this paper is to:

- Discuss the functional anatomy of TMJ for the purpose of aiding in joint injection;

- Summarize various types and techniques of interventional procedures for the TMJ;

- Discuss the use of nerve blocks and interventional procedures including their indications, advantages, and disadvantages in treatment of TMDs.

We present the following article in accordance with the PRISMA-ScR reporting checklist (available at https://joma.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/joma-22-9/rc).

Methods

Search strategy

An electronic search using databases such as PubMed (Medline), Scopus and Google Scholar was performed by 2 researchers: (SPS) and (MK), using free text words and MeSH term including “Temporomandibular Joint Disorders” [MeSH], Temporomandibular Disorders” [MeSH] OR “TMDs”, “Arthrocentesis” [MeSH], “Arthroscopy” [MeSH], “Intraarticular injections”, “Nerve blocks” [MeSH] “Auriculotemporal nerve block” [Mesh], OR ATN block, “Twin block” [MeSH], OR “masseteric nerve block” [MeSH]. In addition, cross references in these articles were also considered whenever applicable. Only those articles or abstracts that were published in English were used to compile this review. The scoping review, systematic review, randomised control trials, case reports/series that were published between January 1st 1974 to December 31st 2021 were included in this review (Table 1, and details of keywords explained in Appendix 1). After selecting the articles, data that were included and extracted were: number of articles included; TMD treated; type of intervention, agents used; assessment and results. Also, additional information regarding technique, advantages, indications and various studies using these techniques were compiled using these articles.

Table 1

| Items | Specification |

|---|---|

| Date of search | 5th Jan 2022 |

| Databases and other sources searched | PubMed (Medline), Scopus and Google Scholar |

| Search terms used | “Temporomandibular Joint Disorders” [MeSH], Temporomandibular Disorders” [MeSH] OR “TMDs”, “Arthrocentesis” [MeSH], “Arthroscopy” [MeSH], “Intraarticular injections”, “Nerve blocks” [MeSH] “Auriculotemporal nerve block” [Mesh], OR ATN block, “Twin block” [MeSH], OR “masseteric nerve block” [MeSH] |

| Timeframe | January 1st, 1974 to December 31st, 2021 |

| Inclusion and exclusion criteria | Inclusion criteria: articles or abstract published in English only |

| Type of article included: the narrative review, systematic review, randomised control trials, case reports/series | |

| Exclusion criteria: articles other than English language, titles and abstracts of those articles that did not fulfil search criteria | |

| Selection process | Independent search was conducted by two authors MK, SPS in indexed databases using MeSH terms. The articles were screened based on title and abstract |

Results

A total of 8,567 articles were identified, with 8,439 were eliminated due to title, type of article, inclusion criteria, and language. Furthermore, selected 128 articles were screened by reading the abstract and full text, with 69 articles being included in the scoping review (Figure 1).

Anatomy of TMJ and pathophysiology of TMDs

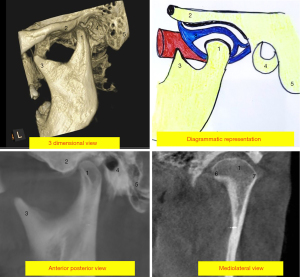

The TMJ is a ginglymus-arthrodial joint that is composed of the condyle, glenoid fossa, articular tubercle, articular disc, retro discal tissue, synovial membrane, and joint capsule (4). Movement occurs in a hinge-like motion (ginglymus), and gliding (arthrodial) motion. Hinge like motion is dominant in the earlier stage of opening in the lower joint compartment, and the sliding movement dominates the later stage of opening in the upper joint compartment. Sliding is also the predominant mechanism of protrusive and lateral movements (5). The joint can be divided into two systems. The first joint system is the tissues that surround the inferior synovial cavity (i.e., the condyle and the articular disc). Because the lateral and medial discal ligaments bind the disc to the lateral and medial poles of the condyle, the only physiologic movement that can occur between these surfaces is sliding of the disc on the condylar articular surface, resulting in hinging motion of the joint. The second system is made up of the condyle-disc complex functioning against the surface of the mandibular fossa. Due to the articular disc’s lax attachment to the articular fossa, sliding movement between these surfaces in the superior cavity is allowed. This is referred to as translation, in which the mandible slides anteriorly and posteriorly. Thus, the articular disc acts as a non-ossified bone contributing to both joint systems, and hence the function of the disc justifies classifying the TMJ as a true compound joint (6). A mass of soft tissue occupies the space behind the disc and condyle. It is often referred to as the posterior attachment. The posterior attachment is a loosely organized system of collagen fibres, branching elastic fibres, fat, blood and lymph vessels, and nerves (7) (Figures 2,3). Discal ligaments restrict the excessive movement of articular disc.

TMD’s are broadly classified in TMJD and masticatory muscle disorders (MMDs) (8,9). TMJD includes joint pain, joint disorders, joint diseases, fractures and congenital or developmental disorders. MMD includes muscle pain, contracture, hypertrophy, neoplasm, movement disorders, and masticatory muscle pain attributed to systemic or central pain disorders. In this article we will be detailing interventional procedures and injections for TMJD (8,9).

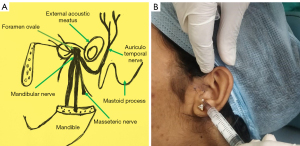

When subjected to constant function, the ligaments can get elongated causing disc to be displaced anteriorly, medially, posteriorly or laterally leading to disc derangements. Further, microtrauma can lead to hypoxia-reperfusion in the articular disc resulting in adhesions in the articular disc leading to its derangement. TMJ is supplied by auriculotemporal nerve (ATN) (branch of posterior division of mandibular nerve), masseteric nerve (branch of anterior division of mandibular nerve) and deep temporal nerve. Hence to perform joint interventions, blocking these nerves is necessary. ATN nerve can be directly blocked by ATN nerve block, whereas masseteric nerve can be blocked directly or as a part of Temporo-Masseteric Nerve Block (TMNB) previously called the Twin block (TB) procedure along with deep temporal nerve (10).

TMJ nerve block and interventional procedures

TMJ interventions can be anesthetic, diagnostic or therapeutic. TMJ nerve blocks can be used to anesthetize the TMJ before other procedures, as in the case of an ATN block before intraarticular steroid injections or manual reduction procedures for TMJ disc displacement without reduction and TMJ luxation. TMJ nerve blocks can be used diagnostically to distinguish TMJ arthralgia from central pain or referred pain from odontogenic and non-odontogenic sources. TMJ interventional nerve blocks and injections may also be used therapeutically for management of various TMD’s such as internal derangements, and degenerative joint disorders. Steroids may be therapeutically injected into TMJ to decrease inflammation. Arthrocentesis may be used to flush and mobilize TMJ (summarized in Table 2) (11).

Table 2

| Intervention | Indication | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATN block | For local anaesthesia while performing TMJ procedure As diagnostic block |

Effective in pain reduction | Delicate joint structures may be traumatized during the procedure |

| Masseteric nerve block and TMNB |

For local anaesthesia while performing TMJ procedure Reduction of TMJ, pain relief in internal derangements |

Relatively safe technique | Temporary loss of blink reflex |

| Arthrocentesis | Chronic joint pain, acute degenerative or rheumatoid arthritis, disc derangements, post traumatic arthritis | Washes out inflammatory mediators; disrupts adhesions; releases disc Increases disc mobility Safe and less invasive procedure |

Pain, edema, transient facial nerve paralysis, bleeding into joint |

| Arthroscopy | Internal derangement, closed lock, osteoarthrosis, pain reduction | Allows direct joint visualization; lavages the joint by removing loose bodies; allows introduction of pharmaceutical agents; breaks adhesion | Tympanic membrane puncture, nerve injury, haemorrhage, hemarthrosis, laceration of cartilage, glenoid fossa perforations and instrument breakage |

| Intracapsular or intraarticular injection | Acute synovitis, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, gout, and psoriatic arthropathy | Less invasive than surgery Can be performed with other joint procedures Provides short term and intermediate term relief in patients who failed with conservative therapies |

Mild pain after injection |

TMJ, temporomandibular joint; ATN, auriculotemporal nerve; TMNB, Temporo-Masseteric Nerve Block.

Preoperative preparation for interventional procedures of TMJ

Patient’s head is covered with head cap and secured with micropore tape or forceps. Hair in the region of interest can be shaved off. Surgical site can be marked for outline of TMJ, reference lines with markers. The interventional sites must be sterilized with 2% chlorhexidine solution or povidone iodine solution for asepsis. Materials required for the interventional procedures of TMJ include syringes, sterilized gauze and cotton, gloves, anesthetics, pharmaceutical agent, saline, arthroscopic equipment (for arthroscopy), markers, micropore tapes, drapes and head caps.

Interventional procedures

ATN block

The ATN is a branch of the posterior division of the mandibular branch of the trigeminal nerve. ATN arises from main trunk and loops middle meningeal artery and then passes backward between lateral pterygoid and neck of the condyle, turning laterally behind the joint. It then passes upward over zygoma and entering temple region. ATN has articular, auricular and superficial temporal branches and articular branch supplies TMJ (Figure 4A). A 27-gauge long needle is inserted into the skin at a point just inferior and anterior the junction of the earlobe and the tragus. The needle is advanced until it reaches the posterior neck of the condyle, then transposed posteriorly until the needle tip passes the posterior side of the condylar neck. As soon as the needle tip contacts the condylar neck, it is rotated antero-medially to a depth of 1 cm, then aspirated. After negative aspiration, the 2% lidocaine with 1:100,000 adrenaline is deposited (Figure 4B) (12-14).

Masseteric nerve block and TMNB

Masseteric nerve, branch of anterior division of mandibular nerve also supplies TMJ. Masseteric nerve passes in close proximity to the roof of the infratemporal fossa reaches to the mandibular notch from above the superior head of the lateral pterygoid. The nerve supplies TMJ and runs in downward and forward direction to innervate masseter muscle. TMJ procedures may necessitate blocking this nerve, which can be accomplished with a masseteric nerve block, which blocks only the masseteric nerve, or a TMNB, which blocks both the masseteric and deep temporal nerves in a single puncture.

For masseteric nerve block, mandibular notch is located with index finger, below zygomatic arch. A 27-gauge needle is inserted to a depth of 1.5 cm, at a point posterior to the index finger. The needle is inserted at an obtuse angle to the condylar neck and directed towards condylar fovea, depositing full carpule of 2% lidocaine with 1:100,000 adrenaline.

For TMNB, 27-gauge long needle, 1.5-inch size attached with 1.8 mL syringe loaded with of 2% lidocaine with 1:100,000 adrenaline is used. It is a supra zygomatic injection. The needle is placed 1cm posterior to the posterior border of the frontal process of the zygomatic bone at a point of depression of the greater wing of the sphenoid bone over the temporal region. The needle is inserted at a 35–45-degree angle to the calvarium, right angle to the zygomatic arch and 1.8mL of solution is deposited after negative aspiration of the syringe (10,15).

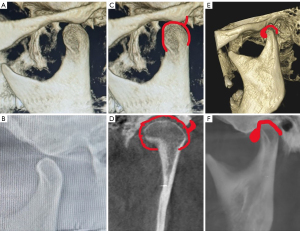

Arthrocentesis

Şentürk and Cambazoğlu classified arthrocentesis into single-puncture and double puncture arthrocentesis (16). Single puncture arthrocentesis has been subclassified as type 1 (single-needle cannula method) and type 2 (single-puncture method using a double or dual-needle cannula). Double puncture arthrocentesis is a traditional method of arthrocentesis using two cannulas and two punctures. Before the arthrocentesis, the TMJ should be anesthetized with ATN block. The patient’s head is held in an upright position and tilted to the opposite side. A reference line drawn from outer canthus of the eye to the tragus (the cantho-tragal line or the Holmlund line). Two points, corresponding to the glenoid fossa and articular eminence should be marked as entry points in reference to this line. The glenoid fossa point is marked at a point 2 mm below the reference line and 10 mm in front of the tragus. Articular eminence point is marked at a point 10 mm below the reference line and 20 mm anterior to the tragus (Figure 5). During this procedure, patient keeps the mandible protruded and mouth wide open. Two needles are used: one to deposit the solution, and the other to allow drainage of the solution. These needles are introduced into the upper joint space. Needle is inserted at an angle of 45 degree at glenoid fossa in a superior, medial and anterior direction, and 2 mL of ringer solution is deposited to distend the upper joint compartment. At the articular eminence point, the second needle is inserted in posteriorly, superiorly and medially. With both needles in position, solution is deposited through the first needle for lavage, while second needle acts as a portal for outflow of lavage materials (17,18). A meta-analysis by Monteiro et al. found no differences between the two techniques in terms of mouth opening or operative time (19).

Arthroscopy

An arthroscopic telescope (1.8–2.6 mm in diameter) with an attached camera is introduced into the upper compartment of the TMJ, and its two-dimensional image is viewed in a monitor. Another access point 10–15 mm anterior to the arthroscope is placed as portal for outflow and instrumentation (20). General or local anaesthetic is used before arthroscopy. If arthroscopy is the only surgery to be performed, local anaesthesia is used; if another procedure is to be performed, general anaesthesia is used. The preferred local anaesthetic is 2% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine. This method, like arthrocentesis, employs the same cantho-tragal reference line. First, a 21-gauge needle is placed at 90 degrees to the skin at a point 12 mm anterior to the tragus and 2 mm below the cantho-tragal referral line with a 10 mL syringe containing saline. To penetrate the superior joint space, the needle is directed anteriorly and superiorly. Another puncture incision is made 5–8 mm anterior to the first point, to insert a sleeved trocar, to which a scope with an eye piece or a chip camera can be attached to visualise the joint space. If there are adhesions or loose bodies in the joint space, they can be removed (21).

Intracapsular or intraarticular injection

Intraarticular injections are given to the upper compartment as they are larger and easy to locate. During the procedure, the TMJ area is prepared using antiseptic, and the mouth is kept in a partially opened position. A 23-gauge needle with a 2 mL syringe is inserted at a point 8 to 10 mm anterior to the tragus and 2 to 3 mm inferior to the zygomatic arch (Figure 6). The needle is introduced into the upper compartment posterior and superior to the lateral pole of the condyle. After reaching the upper compartment, a local anesthetic is injected, the needle is left in place, and the syringe is withdrawn and replaced with one carrying medication. The needle is removed once the medication has been injected, and pressure is applied for 1 to 2 minutes (22,23).

Postoperative instructions: after the above procedure, patient may require administration of analgesics, intermittent ice application for next 48 hours.

Discussion

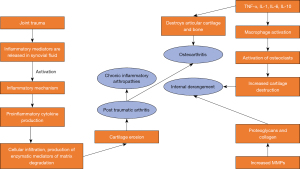

In this review, the existing literature was analysed and various joint interventional procedures are evaluated and explained (Table 3). TMDs are a result of multifactorial causes which are compounded by local, systemic, psychological and structural factors. Trauma and parafunctional habits may initiate the TMD, which is further complicated by dynamic mechanical and muscular disharmony, condition of articular disc and retro discal tissue. These elements act singly or together causing increase in inflammatory mediators, cytokine production, and cartilage destruction, thus altering joint homeostasis and causing arthritic changes, and disc pathologies (Figure 7). These inflammatory mediators, as well as some pathologies like adhesions and loose bodies, can be flushed out or eliminated by these interventional procedures. TMDs produce overlapping symptoms, often challenging the diagnosis and management. Distinguishing site and source of pain are critical for successful management (41-44). Nerve blocks can aid in diagnosis or used before interventional procedures to anesthetise the region or therapeutically in the management of TMDs.

Table 3

| Reference | Number of articles included | TMD | Type of intervention | Agents used | Assessment | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liu Y et al. (24) | 11 RCTs | Temporomandibular osteoarthritis | Intra articular injections | Hyaluronic acid, corticosteroids, corticosteroid plus hyaluronic acid, morphine, tramadol, PDGF, placebo, arthrocentesis alone |

Pain Movements of jaw |

Pain reduction and improved jaw function was excellent in intra articular injections of morphine, tramadol, and PDGF after arthrocentesis Short term benefit of maximal mouth opening was seen with hyaluronic acid intraarticular injections Combination intraarticular injections (corticosteroids and hyaluronic acid) reduced symptoms than when used alone |

| Al-Moraissi EA (25) | 6 (2 RCTs, 2 controlled clinical trials, and 2 retrospective studies) | Internal derangement of TMJ | Arthroscopy vs. Arthrocentesis | Arthroscopy- checked for synovial membrane adhesions and disc perforations; release of adhesion and no other intervention. Arthrocentesis was under local anesthesia; Intra-articular injection with saline, hyaluronidase, or corticosteroids |

Pain Jaw function |

Pain reduction and jaw function improvement was more effective using arthroscopy than arthrocentesis |

| Li DTS et al. (26) | 11 articles: 8 RCTs, 3 prospective clinical studies |

Disc displacement with or without reduction, arthralgia, Wilkes stages 3 and 4, internal derangement | Timing of Arthrocentesis vs. conservative management | 3 groups: Arthrocentesis as the initial treatment, vs. as early treatment vs. late treatment |

Pain Mouth opening |

Beneficial results in all 3 groups when arthrocentesis was done within 3 months of conservative treatment |

| Nagori SA (27) | 12 RCTs, 1 retrospective | Osteoarthritis Disc displacement with or without reduction TMJ inflammatory and degenerative diseases Joint pain |

Arthrocentesis | Single-puncture arthrocentesis (type 1 or 2) vs. double-puncture arthrocentesis | Pain Maximal mouth opening Operating time Needle relocation |

Operating time was less for Single-puncture type-2 arthrocentesis in comparison with the double-puncture method. Operating time difference was insignificant between type-1 single puncture and double-puncture arthrocentesis Single puncture type 2 arthrocentesis had less needle relocation No difference between pain reduction or maximal mouth opening between two techniques |

| Al-Hamed FS et al. (28) | 9 RCTs | Osteoarthritis and disc displacement | Intraarticular injection | Platelet concentrates vs. hyaluronic acid or saline solution | Pain Mouth opening |

In comparison with hyaluronic acid, Platelet concentrate reduces pain 3 months post-treatment In comparison with saline, platelet concentrate reduces pain and increases mouth opening for long term |

| Liu S et al. (29) | 9 RCTs | Anterior disc displacement with or without reduction | Intraarticular injection and TMJ arthrocentesis | Intra-articular analgesic injections used were non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and opioids | Pain Mouth opening |

Statistically insignificant improvement of mouth opening or pain reduction using Intra-articular non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs with TMJ arthrocentesis Statistically significant pain reduction (at 1 week, 1, 3, and 6 months) and mouth opening (at 1 week, 1 and 6 months) using intraarticular injections of opioids with arthrocentesis of TMJ |

| Bouchard C et al. (30) | 5 RCTs | TMJ pain, arthralgia, disc displacement without reduction | Arthrocentesis or arthroscopy vs. nonsurgical treatment | Arthrocentesis and arthroscopy Nonsurgical treatment: soft diet, physiotherapy, splints, NSAIDs, corticosteroids, local analgesics, exercises |

Pain TMJ function- mouth opening, chewing improvement; increased quality of life; complications |

Pain reduction at 6 months and 3 months in intervention group No significant difference in improvement in mouth opening was observed at 6 and 1 month |

| Al-Moraissi EA et al. (31) | 33 RCTs for maximal mouth opening, 36 for pain | Arthrogenous temporomandibular disorders (internal derangement and TMJ osteoarthritis) | Conservative treatment vs. Intra articular injections vs. arthrocentesis vs. arthroscopy vs. open joint surgery | Conservative treatment: exercises, splint therapy Intraarticular injections: hyaluronic acid or corticosteroid arthrocentesis: alone or with pharmaceutical agents Arthroscopy: alone or with HA and PRP open joint surgery: with physiotherapy |

Pain and maximal mouth opening | Combination with intraarticular injection with adjuvant pharmacological agents showed more short and intermediate term effectiveness than conservative treatments in terms of improved mouth opening and pain reduction |

| Nagori SA et al. (32) | 3 RCTs, 2 controlled clinical trials and 1 retrospective study | Closed lock, disk displacement, capsulitis, degenerative joint disease, synovitis | Arthrocentesis with or without splint therapy | Arthrocentesis: 2 needle technique followed by intra articular injection Splint therapy: hard and soft splint |

Pain Mouth opening Mandibular movement: Protrusive movement, lateral movement, chewing ability or life index |

No statistically significant difference in pain reduction or maximal mouth opening after arthrocentesis with or without splint therapy |

| Monteiro JLGC et al. (19) | 9 | Disc displacements with or without reduction Degenerative and inflammatory joint disease Osteoarthritis |

Arthrocentesis | Single puncture arthrocentesis (type 1 and type II) vs. double puncture arthrocentesis | Pain Mouth opening Operative time |

No statistical difference in improvement of mouth opening between single and double puncture arthrocentesis Double puncture arthrocentesis showed slightly better results in terms of pain reduction No statistically significant difference between operative time of type 1 single puncture arthrocentesis compared to double puncture arthrocentesis |

| Chung PY et al. (33) | 5 RCTs | Osteoarthritis | Intraarticular injection after arthroscopy or arthrocentesis | Platelet rich plasma vs. placebo (hyaluronic acid, saline, or no injection |

Pain Mouth opening |

Pain reduction was better in plasma rich platelet injection compared to placebo. No difference in mouth opening in both groups |

| Liu Y et al. (34) | 8 RCTs | Osteoarthritis of TMJ | Intraarticular injection | Corticosteroid vs. hyaluronic acid or placebo | Pain Mouth opening |

Pain reduction was better with corticosteroid injections with arthrocentesis compared to placebo in the long-term, but was inferior in improving mouth opening Reduction in pain and improved mouth opening in both Corticosteroid and hyaluronate injections without arthrocentesis; however success rate of the corticosteroid group significantly lower than the hyaluronate group |

| Reston JT et al. (35) | Prospective case series: 11, retrospective comparative study: 16, RCTs: 3 |

Disc displacement with or without reduction Degenerative joint disease |

Surgical techniques | Arthrocentesis, arthroscopy, discectomy without replacement, or disc repair/repositioning | Pain Mouth opening |

For disc displacement without reduction, arthroscopy and arthrocentesis were effective significantly Highest improvement rate was statistically significant for disc repair/repositioning |

| Haigler MC et al. (36) | 5 (3 RCTs; 2 CTs) | Osteoarthritis | Intraarticular injection | Study group: platelet-rich plasma or platelet-rich growth factor intraarticular injection Control group: no injection or saline injection or hyaluronic acid injection |

Pain Mouth opening |

No significant improvement in mouth opening in platelet-rich plasma or platelet-rich growth factor intraarticular injection group or control group or hyaluronic acid group Pain reduction was favorable in platelet-rich plasma or platelet-rich growth factor intraarticular injection group or control group or hyaluronic acid group |

| Vos LM et al. (37) | 3 RCTs | TMJ arthralgia Disc displacement without reduction, closed lock |

TMJ lavage vs. nonsurgical treatment | TMJ lavage: arthroscopy and arthrocentesis Nonsurgical: medical treatment, splint therapy, hot packs, exercises, physical therapy |

Pain Mandibular range of movements |

The statistically significant difference in pain reduction in TMJ lavage group. No difference in mouth opening improvement in both groups |

| Sakalys D et al. (23) | 2 RCTs | Anterior disc displacement with or without reduction Osteoarthritis |

Intraarticular injections with arthroscopy | Intraarticular injections used were plasma rich in growth factors and hyaluronic acid, followed by arthroscopy | Pain | Statistically significant pain reduction in plasma rich in growth factors intraarticular injections group compared with hyaluronic acid injections Pain management was better with intraarticular injections followed by TMJ arthroscopy |

| Moldez MA et al. (38) | 7 RCTs | Arthritis Disc displacement with or without reduction Intracapsular TMDs Osteoarthritis |

Intraarticular injection | Hyaluronic acid vs. corticosteroids | Pain | No statistical difference between hyaluronic acid or corticosteroids in pain reduction, but hyaluronic acid was better than placebo |

| Li F et al. (39) | 6 RCTs | Osteoarthritis of TMJ | Intraarticular injection | Platelet rich plasma vs. placebo or hyaluronic acid | Pain | Pain reduction in platelet rich plasma injection group was more effective than placebo (at 6 months and 12 months post injection) Statistically significant pain reduction in platelet rich plasma injection group compared with hyaluronic acid injections at 12 months post injection |

| Li C et al. (40) | 4 RCTs | Disc displacement with or without reduction Inflammatory and osteoarthritis |

Intraarticular drug injection of Inferior or double TMJ spaces versus superior TMJ space | Hyaluronic acid and corticosteroid | Pain Mouth opening |

Significantly increase in mouth opening and pain reduction in inferior or double spaces intraarticular injection technique compared with superior space injection technique, inferior or double spaces intraarticular injection technique were beneficial in long term than superior space injection |

TMD, temporomandibular disorder; RCT, randomized control trial; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor; TMJ, temporomandibular joint; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; HA, hyaluronic acid; PRP, platelet rich plasma; CT, control trial.

TMJ interventions when performed under local anesthesia, requires ATN block and masseteric nerve block to temporarily anesthetize the region. The ATN block eliminates pain temporarily, differentiates primary pain from referred pain, differentiates true joint pain from other pain such as pain originating from muscles, odontogenic causes or central pain (12,13). It is useful before invasive treatment to rule out if the TMJ is involved or not. This block also decreases pain and protective muscle splinting, which helps in achieving increased range of motion. It helps in other therapies such as joint exercises and therapeutic injections (14). Zhou et al. found satisfactory outcome in patients with closed lock when ATN block was performed along with mandibular exercises (13) Majumdar blocked the ATN before interventional procedures for hypermobility of the TMJ (14). Demirsoy et al. investigated efficacy of ATN block as a conjunction therapy along with conservative therapy in 22 patients with disc displacements and found significant differences in mouth opening and pain reduction at regular post treatment follow ups (12).

Masseteric nerve block suppresses sensory impulses from masseter muscle and is indicated for pain, myalgia, soreness, spasm of masseter muscle origin, protractive muscle splinting, chronic masseter muscle pain, subluxation and mandibular dislocations. Masseteric nerve is blocked effectively along with deep temporal nerve through extraoral approach via TMNB (45). For TMJDs, Young used TMNB for the reduction of resistant unilateral dislocated condyle which allowed minimally painful reduction of condyle (46) and recently it has also been reported to be effective in relieving pain in an internal derangement case of disc displacement without reduction (47). TNMB effectively reduces pain and improves jaw functions as it blocks both sensory and motor components of the nerve (48). Although a relatively safe technique without complications, temporary loss of blink reflex can occur due to anaesthesia of the temporal branch of the facial nerve as a result of penetration of anaesthetic agent into the parotid facia.

Arthroscopy involves direct visualization of the upper compartment of the joint using two ports; in one port a scope can be attached to visualize the joint, while small instruments pass through the other. Certain interventions such as washing out the joint, removing loose bodies, introducing pharmaceutical agents and breaking adhesion can be performed by skilled surgeons (49,50). Arthroscopy can be performed in cases of internal derangement, closed lock and osteoarthrosis. Arthroscopy allows inspection of the synovial lining, disc, articular cartilage, adhesions, loose bodies, perforation of the disc, and attachment of the disc. This procedure increases mandibular range of movement by improving disc mobility, and helps in pain reduction (20). Abboud et al. evaluated the efficacy and safety of lysis and lavage of the TMJ through arthroscopy in 47 patients with chronic close lock and found a 77% success rate with increased maximal mouth opening (21). Although a relatively safe procedure, some complications such as puncture of the tympanic membrane, nerve injury, hemorage, hemarthrosis, laceration of cartilage, glenoid fossa perforations and instrument breakage are some of the complications encountered (51). González-García encountered otologic, ocular and neurologic complications in 670 joints with TMJ derangement who underwent arthroscopy (52).

Arthrocentesis is an interventional procedure involving lavage of the TMJ, washing out inflammatory mediators, releasing the articular disc, and disrupting adhesions. The mechanism behind arthrocentesis is through the flushing out of inflammatory mediators that accumulate during the diseases process, such as interleukin (IL)-1, IL-2, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha, and cytotoxins (53). Arthrocentesis distends the joint space and disrupts adhesions in the disc (54). It eliminates negative pressure (55) and decreases intraarticular pressure (56). Also, arthrocentesis improves disc mobility, decreasing intraarticular surface friction (57,58). Although a relatively safe and less invasive procedure, pain, edema, transient facial nerve paralysis due to local anesthetic, injury to the superficial temporal artery, and bleeding into joint have been reported (59). As it is a blind needle insertion, difficulty in 2 needle insertion may be encountered. Literature reports 2–10% of arthrocentesis procedures have complications (17,57). However, this interventional procedure has low morbidity, is minimally invasive, economical, and remove synovial degradation products. Its reported success rate is 70–90% (59-61). Arthrocentesis is indicated in osteoarthritis (54), chronic joint pain (57), acute episodes of degenerative or rheumatoid arthritis (18), painful disc displacement with reduction (18), and post traumatic arthritis (62). Malachovsky et al. observed arthrocentesis reduces pain, need of analgesics, and improves mobility of joint (56). Arthrocentesis increased mouth opening and reduced pain without any complication and morbidity in 76 patients with internal derangement of TMJ (63).

A systematic review and meta-analysis comparing arthrocentesis and arthroscopy concluded that although high level evidence is lacking, arthroscopy may be slightly better that arthrocentesis for improving joint movement and reducing in pain in cases of internal derangement of TMJ while complications were similar in both procedures (25). Another systematic review had conflicting reports and suggested that there is lack of strong evidence and they should be advised with caution (30). Although insignificant clinically, they may have a better outcome in reducing pain in comparison to non-surgical modalities and they can be considered in patients refractory to conservative therapies (35,37,64). Among, different arthrocentesis techniques (single puncture and double puncture) both were equally effective in reducing pain and improving mouth opening (19,27). Most of the reported complications were temporary and resolved with no treatment (65).

Intracapsular or intraarticular injection is a therapeutic injection of a pharmaceutical agent into the TMJ. It is less invasive than surgery and can be performed with arthroscopy and arthrocentesis for better results (23). Various medications (Table 4), including corticosteroids, morphine, tramadol, sodium hyaluronate (low or high molecular weight), and platelet-rich plasma have been administered alone or in combination to treat acute synovitis, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, gout, and psoriatic arthropathy. Liu et al. conducted a meta-analysis using various intraarticular injections for TMJ osteoarthritis and found effectiveness with tramadol, morphine and PDGF after arthrocentesis in reducing pain and improving mouth opening. While hyaluronic acid injection alone improves mouth opening, the combination of corticosteroid and hyaluronic acid injection reduces symptoms of both pain and improves mouth opening (24). Sakalys et al. found that subjects who received intraarticular injections of plasma rich in growth factors had statistically significant pain relief compared to hyaluronidase injections (23). Ok et al. used intra-articular injections of growth hormone in rat TMJs and found that growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor-1 concentrations were higher after local injections of growth hormone in comparison to controls, implying that growth hormone injections into the TMJ cartilage and subchondral bone reduced osteoarthritis scores in rats and that growth hormone injections for humans could be used in the future (66). Chandra et al. found that intraarticular injection of platelet rich plasma were more effective in symptom reduction and improving mouth opening than arthrocentesis in 52 patients who had refractory TMDs (67). De Sousa BM used various treatment modalities such as splint therapy, intraarticular injections with betamethasone, sodium hyaluronate, or platelet-rich plasma to treat TMDs and found long term success using combined treatment of splint and intraarticular injection of platelet rich plasma (22). A systematic review comparing various pharmacological agents including hyaluronic acid, morphine, dexamethasone, tramadol, placebo, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), prednisolone, betamethasone, betamethasone plus hyaluronic acid, arthrocentesis alone administered with intra articular injections concluded that injections of morphine, tramadol, PDGF after arthrocentesis improved pain and joint function in TMJ osteoarthritis. A combination of hyaluronic acid and corticosteroids was more effective in improving TMJ osteoarthritis symptoms than corticosteroids alone and hyaluronic acid alone was effective in improving mouth opening in short term (22). Corticosteroids may be indicated more for TMJ pain rather than for improving joint function and mouth opening Intra articular injections of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) and opioids suggest low quality evidence that NSAIDS do not have any effect on pain and mouth opening related treatment outcomes while opioids may improve both in short term (34). Recent evidence also suggests that minimally invasive procedures with intra articular injections may be considered early in the short term (<5 months) and intermediate period (up to 4 years) for relief of symptoms in TMJD patients who do not respond to conservative measures. or within a period of 3 months after conservative treatment (29).

Table 4

| Type of pharmaceutical agent used in intraarticular injection | Mechanism of action | Dose |

|---|---|---|

| Corticosteroid | Powerful anti-inflammatory agent Inhibits pro inflammatory cytokine and enzyme expression Enhances IL-10, IL-1 receptor antagonists expression Activation of serotonin |

Methyl prednisolone (20 mg in 0.5 to 1.0 mL suspension) Combination of betamethasone acetate and betamethasone phosphate (3 mg)—choice of drug for TMJ |

| Hyaluronidase | Maintains joint homeostasis Lubricates joint and balances distribution of stress, prostaglandin E2 and MMP synthesis is reduced, modulation of leukocyte function Anti-inflammatory Decreases mechanical wear and intraarticular fibrosis Hyaluronic acid maintains joint viscosity, and nutrition Hyaluronic acid is present in cartilaginous tissue and synovial fluid |

High molecular weight (7×103 kD) sodium hyaluronate containing 8 mg/mL 2 injections at 1 week interval can be given Given in cases of inflammatory degenerative joint disease |

| Platelet concentrates | Contains growth factors in high concentration Contains cytokines Anti-inflammatory property Cell proliferation stimulation Accelerates cell differentiation Promotes healing process and cell repair |

0.6 mL of PRPPRP is prepared by using citrated 10 mL of patient’s venous blood and centrifugating for 15 min at 1,800 rpm followed by harvesting plasma rich layer at centrifuge at 3,500 rpm for 10 min Platelet concentrates—they are obtained from whole blood of patient; they can be 3 types: 1. plasma rich in growth factors; 2. platelet rich fibrin; or 3. platelet rich plasma |

| Morphine | Nociceptive neuron membrane becomes hyperpolarized, anti-inflammatory | 0.1/1.0 mg |

| Tramadol | 5-HT production is reduced Anti-inflammatory Decreased production of inflammatory cytokines Reduced leukocyte migration |

50 mg/mL |

IL, interleukin; TMJ, temporomandibular joint; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; PRP, platelet rich plasma; 5-HT, 5-hydroxytryptamine.

Arthrocentesis or arthroscopy with injection of hyaluronic acid or Ringer’s lactate solution or without an intra-articular injection in comparison to intra-articular platelet rich plasma (PRP) injections or platelet rich growth factors (PRGF) injections in patents with TMD simultaneously or after arthroscopy or arthrocentesis concluded that PRP or PGRP may be slightly better to reduce post-operative pain and improve TMJ function, but the results were not statistically significant and Type C recommendation may be given (25,26,68).

Another systematic review concluded that platelet concentrates may be slightly more effective than hyaluronic acid in improving pain in the initial 3 months but firm conclusion and evidence require further studies as there were variations in the methods of platelet concentrate preparation which may lead to varied results (27,28). Intra articular injections may also be used following arthroscopy and a systematic review suggests that PRP may be beneficial although there are limited studies (23). Limited evidence also suggests that splint therapy in conjunction with arthrocentesis may not confer additional benefits in comparison to arthrocentesis alone at 1 month. However, well designed studies with longer follow-up are essential to derive firm conclusions (27).

A systematic review and meta-analysis by Nogueira et al. comparing arthroscopy and arthrocentesis reported that there was no significant increase in adverse effects between the two procedures and the adverse effects when present were temporary (65). Complications may include nerve injuries, optical injuries, breakage of the intra-articular instruments, otological injuries, vagal alteration, leakage of fluid into deep cervical tissues, vascular injuries and vertigo (69). Complications of arthroscopy were reported in 4% and most important ones included temporary frontal paralysis, prolonged cervical edema, and arthrocentesis complications (3%) included severe bradycardias, prolonged cervical edema. Complications were often related to the surgeon experience and most of the reported complications were temporary that resolved with no treatment (31).

Limitations of this review

Only PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar were used in this review. Furthermore, the articles included in this review were selected by manually that fulfilled inclusion and exclusion criteria. As a result, even if a comprehensive search was conducted, many articles may have been overlooked. Although this research includes descriptive analysis, no clear conclusions can be drawn because metanalysis was not included.

Conclusions

Diagnosis and management of TMDs are often challenging. Conservative methods are often accepted by patients, while surgical modalities are invasive and involve higher risks for more serious adverse outcomes. Hence TMJ injections are useful, economical, and less invasive methods of joint treatment with good success rates and should be performed in resistant cases with failure of conservative modalities before invasive surgical procedures are considered. If carefully performed by a skilled operator with knowledge of the local anatomy, these interventions are relatively safe. Intraarticular injections with or without arthroscopy and arthrocentesis for better results may be considered for immediate and long-term benefits in cases not responding to conservative modalities.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Archana S and Dr. Nikitha Sridhar for clinical figures 4 and 6.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the editorial office, Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Anesthesia for the series “Orofacial Pain: Diagnostic and Therapeutic Topicals, Nerve Blocks and Trigger Point Injection”. The article has undergone external peer review.

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the PRISMA-ScR reporting checklist. Available at https://joma.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/joma-22-9/rc

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://joma.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/joma-22-9/coif). The series “Orofacial Pain: Diagnostic and Therapeutic Topicals, Nerve Blocks and Trigger Point Injection” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. MK serves as an unpaid editorial board member of Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Anesthesia from July 2021 to June 2023, and served as the unpaid Guest Editor of the series. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work by ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Health Care Services; et al. Temporomandibular Disorders: Priorities for Research and Care. Yost O, Liverman CT, English R, et al, editors. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2020.

- Kalladka M, Young A, Khan J. Myofascial pain in temporomandibular disorders: Updates on etiopathogenesis and management. J Bodyw Mov Ther 2021;28:104-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Randolph CS, Greene CS, Moretti R, et al. Conservative management of temporomandibular disorders: a posttreatment comparison between patients from a university clinic and from private practice. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1990;98:77-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yılmaz D, Kamburoğlu K. Comparison of the effectiveness of high resolution ultrasound with MRI in patients with temporomandibular joint dısorders. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2019;48:20180349. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alomar X, Medrano J, Cabratosa J, et al. Anatomy of the temporomandibular joint. Semin Ultrasound CT MR 2007;28:170-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ahmad M, Schiffman EL. Temporomandibular Joint Disorders and Orofacial Pain. Dent Clin North Am 2016;60:105-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gauer RL, Semidey MJ. Diagnosis and treatment of temporomandibular disorders. Am Fam Physician 2015;91:378-86. [PubMed]

- Young A, Gallia S, Ryan JF, et al. Diagnostic Tool Using the Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders: A Randomized Crossover-Controlled, Double-Blinded, Two-Center Study. J Oral Facial Pain Headache 2021;35:241-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schiffman E, Ohrbach R, Truelove E, et al. Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD) for Clinical and Research Applications: recommendations of the International RDC/TMD Consortium Network and Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group. J Oral Facial Pain Headache 2014;28:6-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Quek SYP, Gomes-Zagury J, Subramanian G. Twin Block in Myogenous Orofacial Pain: Applied Anatomy, Technique Update, and Safety. Anesth Prog 2020;67:103-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu F, Steinkeler A. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of temporomandibular disorders. Dent Clin North Am 2013;57:465-79. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Demirsoy MS, Erdil A, Tümer MK. Evaluation of the Efficacy of Auriculotemporal Nerve Block in Temporomandibular Disorders. J Oral Facial Pain Headache 2021;35:326-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhou H, Xue Y, Liu P. Application of auriculotemporal nerve block and dextrose prolotherapy in exercise therapy of TMJ closed lock in adolescents and young adults. Head Face Med 2021;17:11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Majumdar SK, Krishna S, Chatterjee A, et al. Single Injection Technique Prolotherapy for Hypermobility Disorders of TMJ Using 25% Dextrose: A Clinical Study. J Maxillofac Oral Surg 2017;16:226-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Quek S, Young A, Subramanian G. The twin block: a simple technique to block both the masseteric and the anterior deep temporal nerves with one anesthetic injection. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2014;118:e65-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Şentürk MF, Cambazoğlu M. A new classification for temporomandibular joint arthrocentesis techniques. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2015;44:417-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tvrdy P, Heinz P, Pink R. Arthrocentesis of the temporomandibular joint: a review. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub 2015;159:31-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chang CL, Wang DH, Yang MC, et al. Functional disorders of the temporomandibular joints: Internal derangement of the temporomandibular joint. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2018;34:223-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Monteiro JLGC, de Arruda JAA, Silva EDOE, et al. Is Single-Puncture TMJ Arthrocentesis Superior to the Double-Puncture Technique for the Improvement of Outcomes in Patients With TMDs? J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2020;78:1319.e1-1319.e15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Castaño-Joaqui OG, Cano-Sánchez J, Campo-Trapero J, et al. TMJ arthroscopy with hyaluronic acid: A 12-month randomized clinical trial. Oral Dis 2021;27:301-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abboud W, Nadel S, Yarom N, et al. Arthroscopy of the Temporomandibular Joint for the Treatment of Chronic Closed Lock. Isr Med Assoc J 2016;18:397-400. [PubMed]

- Sousa BM, López-Valverde N, López-Valverde A, et al. Different Treatments in Patients with Temporomandibular Joint Disorders: A Comparative Randomized Study. Medicina (Kaunas) 2020;56:113. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sakalys D, Dvylys D, Simuntis R, et al. Comparison of Different Intraarticular Injection Substances Followed by Temporomandibular Joint Arthroscopy. J Craniofac Surg 2020;31:637-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu Y, Wu JS, Tang YL, et al. Multiple Treatment Meta-Analysis of Intra-Articular Injection for Temporomandibular Osteoarthritis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2020;78:373.e1-373.e18. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Al-Moraissi EA. Arthroscopy versus arthrocentesis in the management of internal derangement of the temporomandibular joint: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2015;44:104-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li DTS, Wong NSM, Li SKY, et al. Timing of arthrocentesis in the management of temporomandibular disorders: an integrative review and meta-analysis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2021;50:1078-88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nagori SA, Bansal A, Jose A, et al. Comparison of outcomes with the single-puncture and double-puncture techniques of arthrocentesis of the temporomandibular joint: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. J Oral Rehabil 2021;48:1056-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Al-Hamed FS, Hijazi A, Gao Q, et al. Platelet Concentrate Treatments for Temporomandibular Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JDR Clin Trans Res 2021;6:174-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu S, Hu Y, Zhang X. Do intra-articular injections of analgesics improve outcomes after temporomandibular joint arthrocentesis?: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Oral Rehabil 2021;48:95-105. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bouchard C, Goulet JP, El-Ouazzani M, et al. Temporomandibular Lavage Versus Nonsurgical Treatments for Temporomandibular Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2017;75:1352-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Al-Moraissi EA, Wolford LM, Ellis E 3rd, et al. The hierarchy of different treatments for arthrogenous temporomandibular disorders: A network meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2020;48:9-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nagori SA, Jose A, Roy Chowdhury SK, et al. Is splint therapy required after arthrocentesis to improve outcome in the management of temporomandibular joint disorders? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2019;127:97-105. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chung PY, Lin MT, Chang HP. Effectiveness of platelet-rich plasma injection in patients with temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2019;127:106-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu Y, Wu J, Fei W, et al. Is There a Difference in Intra-Articular Injections of Corticosteroids, Hyaluronate, or Placebo for Temporomandibular Osteoarthritis? J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2018;76:504-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Reston JT, Turkelson CM. Meta-analysis of surgical treatments for temporomandibular articular disorders. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2003;61:3-10; discussion 10-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Haigler MC, Abdulrehman E, Siddappa S, et al. Use of platelet-rich plasma, platelet-rich growth factor with arthrocentesis or arthroscopy to treat temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis: Systematic review with meta-analyses. J Am Dent Assoc 2018;149:940-952.e2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vos LM, Huddleston Slater JJ, Stegenga B. Lavage therapy versus nonsurgical therapy for the treatment of arthralgia of the temporomandibular joint: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Orofac Pain 2013;27:171-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moldez MA, Camones VR, Ramos GE, et al. Effectiveness of Intra-Articular Injections of Sodium Hyaluronate or Corticosteroids for Intracapsular Temporomandibular Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Oral Facial Pain Headache Winter;32:53–66.

- Li F, Wu C, Sun H, et al. Effect of Platelet-Rich Plasma Injections on Pain Reduction in Patients with Temporomandibular Joint Osteoarthrosis: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Oral Facial Pain Headache 2020;34:149-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li C, Zhang Y, Lv J, et al. Inferior or double joint spaces injection versus superior joint space injection for temporomandibular disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2012;70:37-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kalladka M, Ananthan S, Eliav E, et al. Orbital pseudotumor presenting as a temporomandibular disorder: A case report and review of literature. J Am Dent Assoc 2018;149:983-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kalladka M, Al-Azzawi O, Heir GM, et al. Hemicrania continua secondary to neurogenic paravertebral tumor- a case report. Scand J Pain 2022;22:204-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kalladka M, Alhasan H, Morubagal N, et al. Orofacial complex regional pain syndrome. J Oral Sci 2020;62:455-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kalladka M, Thondebhavi M, Ananthan S, et al. Myofascial pain with referral from the anterior digastric muscle mimicking a toothache in the mandibular anterior teeth: a case report. Quintessence Int 2020;51:56-62. [PubMed]

- Quek SYP, Kalladka M, Kanti V, et al. A new adjunctive tool to aid in the diagnosis of myogenous temporomandibular disorder pain originating from the masseter and temporalis muscles: Twin-block technique. J Indian Prosthodont Soc 2018;18:181-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Young AL, Khan J, Thomas DC, et al. Use of masseteric and deep temporal nerve blocks for reduction of mandibular dislocation. Anesth Prog 2009;56:9-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ananthan S, Subramanian G, Patel T, et al. The twin block injection: an adjunctive clinical aid for the management of acute arthrogenous temporomandibular joint dysfunction. Quintessence Int 2020;51:330-3. [PubMed]

- Ananthan S, Kanti V, Zagury JG, et al. The effect of the twin block compared with trigger point injections in patients with masticatory myofascial pain: a pilot study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2020;129:222-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Murakami K, Ono T. Temporomandibular joint arthroscopy by inferolateral approach. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1986;15:410-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McCain JP, de la Rua H, LeBlanc WG. Puncture technique and portals of entry for diagnostic and operative arthroscopy of the temporomandibular joint. Arthroscopy 1991;7:221-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury SKR, Saxena V, Rajkumar K, et al. Complications of Diagnostic TMJ Arthroscopy: An Institutional Study. J Maxillofac Oral Surg 2019;18:531-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- González-García R, Rodríguez-Campo FJ, Escorial-Hernández V, et al. Complications of temporomandibular joint arthroscopy: a retrospective analytic study of 670 arthroscopic procedures. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2006;64:1587-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Soni A. Arthrocentesis of Temporomandibular Joint- Bridging the Gap Between Non-Surgical and Surgical Treatment. Ann Maxillofac Surg 2019;9:158-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bergstrand S, Ingstad HK, Møystad A, et al. Long-term effectiveness of arthrocentesis with and without hyaluronic acid injection for treatment of temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis. J Oral Sci 2019;61:82-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Leibur E, Jagur O, Voog-Oras Ü. Temporomandibular joint arthrocentesis for the treatment of osteoarthritis. Stomatologija 2015;17:113-7. [PubMed]

- Malachovsky I, Statelova D, Stasko J, et al. Therapeutic effects of arthrocentesis in treatment of temporomandibular joint disorders. Bratisl Lek Listy 2019;120:235-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marzook HAM, Abdel Razek AA, Yousef EA, et al. Intra-articular injection of a mixture of hyaluronic acid and corticosteroid versus arthrocentesis in TMJ internal derangement. J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg 2020;121:30-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- AbdulRazzak NJ. Sadiq JA, Jiboon AT. Arthrocentesis versus glucocorticosteroid injection for internal derangement of temporomandibular joint. Oral Maxillofac Surg 2021;25:191-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Santos GS, Sousa RC, Gomes JB, et al. Arthrocentesis procedure: using this therapeutic maneuver for TMJ closed lock management. J Craniofac Surg 2013;24:1347-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nitzan DW, Samson B, Better H. Long-term outcome of arthrocentesis for sudden-onset, persistent, severe closed lock of the temporomandibular joint. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1997;55:151-7; discussion 157-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hosaka H, Murakami K, Goto K, et al. Outcome of arthrocentesis for temporomandibular joint with closed lock at 3 years follow-up. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 1996;82:501-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Park JY, Lee JH. Efficacy of arthrocentesis and lavage for treatment of post-traumatic arthritis in temporomandibular joints. J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg 2020;46:174-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Briggs KA, Breik O, Ito K, et al. Arthrocentesis in the management of internal derangement of the temporomandibular joint. Aust Dent J 2019;64:90-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cavalcanti do Egito Vasconcelos B, Bessa-Nogueira RV, Rocha NS. Temporomandibular joint arthrocententesis: evaluation of results and review of the literature. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol 2006;72:634-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nogueira EFC, Lemos CAA, Vasconcellos RJH, et al. Does arthroscopy cause more complications than arthrocentesis in patients with internal temporomandibular joint disorders? Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2021;59:1166-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ok SM, Kim JH, Kim JS, et al. Local Injection of Growth Hormone for Temporomandibular Joint Osteoarthritis. Yonsei Med J 2020;61:331-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chandra L, Goyal M, Srivastava D. Minimally invasive intraarticular platelet rich plasma injection for refractory temporomandibular joint dysfunction syndrome in comparison to arthrocentesis. J Family Med Prim Care 2021;10:254-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez IQ, Sábado-Bundó H, Gay-Escoda C. Intraarticular injections of platelet rich plasma and plasma rich in growth factors with arthrocenthesis or arthroscopy in the treatment of temporomandibular joint disorders: A systematic review. J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg 2021; Epub ahead of print. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tozoglu S, Al-Belasy FA, Dolwick MF. A review of techniques of lysis and lavage of the TMJ. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2011;49:302-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Shastry SP, Susainathan A, Young A, Ramdoss T, Narayan Gowda NK, Kalladka M. Nerve blocks and interventional procedures in the management of temporomandibular joint disorders: a scoping review. J Oral Maxillofac Anesth 2022;1:28.